4 Ridiculous Comments that Almost Killed a $12 Billion Week

...and how the very best investors avoid these common misbeliefs

Last week was a $12 billion week.

Auth0, Rocket Lab and Spire just announced exits totaling $12 billion. While at Bessemer Venture Partners, I co-led each of these initial investments in the 12-month timeframe between July 2014 and June 2015 (I left to launch Ubiquity Ventures in mid-2017).

The Auth0 founding team of Eugenio Pace and Matias Woloski and former CEO Jon Gelsey grew their developer tools startup to a $6.5 billion purchase by Okta that was announced last Wednesday, March 3. While at Bessemer, I partnered with this team at the seed stage in June 2014 by leading their $2 million seed round and personally serving as their first board member. This seed investment was made at an $8m pre-money valuation - Bessemer just published that actual seed investment memo.

Rocket Lab founder Peter Beck and his team grew their rocket launch startup to the point that it will go public via SPAC at an estimated $4 billion valuation as announced last Monday, March 1. Bessemer’s David Cowan and I co-led this December 2014 investment and were both part of Rocket Lab’s board.

The Spire founding team of Peter Platzer, Jeroen Cappert, and Joel Spark have grown their data-focused small satellite constellation startup to the point that it will go public via SPAC at an estimated $1.6 billion valuation as announced last Monday, March 1. David Cowan and I co-led this June 2015 investment and were both part of Spire’s board (with extra thanks to Josh Benamram for his work on diligence and the broader Bessemer space roadmap).

Warning: Ridiculous Comments Ahead

In the 7 years between these initial investments and last week’s $12 billion of exits, people have said some ridiculous things to me. Here I will try to make sense of some of these ridiculous statements, analyze why they were so incorrect, and suggest what this means for the savviest investors.

#1 - “Sunil, you’re so lucky you get to invest in cool things. I have to invest in things that actually make money.”

Many VCs have said this to me during my time at Bessemer (2011-2017) and continue to do so with Ubiquity Ventures. Today, I do have early investments that put software in space, software on cows, software in cars, and more. Yes it is pretty cool to make software ubiquitous. But it’s the suggestion that these kind of startups don’t make money that makes this comment ridiculous:

Let’s start with the data: Auth0 will reportedly end this year with $200 million ARR (annual recurring revenue). Rocket Lab is forecasting $69 million of revenue this year and to date has successfully launched ~100 satellites to Earth orbit. Spire reported $36 million of ARR as of the end of last year. In 2014, despite the fact that these companies did not pretend to look like the next Snapchat or Salesforce.com, they were innovative companies focused on high-growth revenue, and, in this regard, they have largely succeeded.

Now back to this particular ridiculous comment. The VC industry can often devolve into the model of little kids playing soccer where investors abandon their field positions to chase the ball wherever it goes. It is these hotter investment sectors that “make a lot of sense” that draw in the majority of venture capital investment and broader attention — as measured by Gartner reports, TechCrunch conferences or viral tweets.

However, by the time a sector has garnered so much buzz, the attractive investment opportunities are gone. It was Stanford professor Jeffrey Pfeffer who wrote, “You can’t do normal things and expect abnormal returns.” It is precisely because these investment areas feel so lucrative that they are not.

Hot sectors attract massive amounts of venture capital which bid up startup valuations. At best, this compresses investment returns and at worst it creates a hyper-competitive industry of startups with “capital cannons” (to use Masa at Softbank’s mafia-style phrasing) aimed at one another. The lesson here, as one of my favorite Ubiquity LPs Chris Douvos like to say, is to “optimize one’s discomfort” as opposed to chasing the comfortable.

The challenge is to find investment areas that don’t make sense to most but can be thoughtfully reasoned through — as in developer tools like Auth0 in 2014 and newspace companies like Rocket Lab and Spire in 2015.

#2 - “Sunil, didn’t a rocket just blow up last week. Rocket Lab must be risky.”

Yes they did blow up. Two in fact. Just months before we chose to invest over $10 million in Rocket Lab.

At Bessemer, David Cowan and I invested in Rocket Lab in November 2014. Just the month before (October 2014), another company’s rocket exploded (an Orbital Sciences Antares in Wallops, VA). Two months before that, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket exploded.

If two rockets just exploded recently, then rockets must be risky and rocket startups must be risky. Right? There are two fundamental flaws here that lead to this ridiculous comment:

First a single sample is not the same as the underlying distribution. I find that it’s often the insurance industry that knows the most about failure rates and their distributions. In this case, they peg rocket launch failures at about a 5% rate. We know rockets fail 5% of the time. What happened with Antares and Falcon 9 in 2014 were the unfortunate events that define the 5% category. However, across 110 launches to date, the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket has a 98% success rate.

So while it’s scary to see 2 rocket failures in 2 months, it is important to go back to the broader distribution rather than making decisions based on single events/samples. Annie Duke’s book “Thinking in Bets” covers this topic in spades.

Second, this failure rate of rocket launches should not be conflated with the failure rate of rocket startups. The rocket launch failure rate reflects the large number of systems that need to operate in concert to have a successful launch.

Rocket startup company failure rate reflects how well a visionary founder (like Peter Beck of Rocket Lab) can navigate a slew of startup challenges to find product-market fit and create scale before running out of money.

#3 - “Sunil, you’re too young to remember, but Iridium lost $5 billion in the ‘90s, so space is hard.”

One of the best things about the startup world is that experience doesn’t matter that much.

Sometimes experience gets in the way and the lack of it can enables a newbie to disrupt an industry. Ignoring what “everyone knows” can be an asset. I believe that with startups, it’s so important to forget the lessons of the past that IdeaLab’s Bill Gross and I co-authored a Ubiquity blog post titled “Why We Must Never Forget to Keep Forgetting”. In it, we propose forgetting the generalizations and folktales and instead using the “right way to remember” the past. The example of grocery delivery startup Webvan and its 1999 spectacular demise could have deterred the 2012 launch of Instacart. However, by digging deeper into the reasons why Webvan failed, we can assess whether any of those elements have changed. In the time between 1999 to 2012, internet penetration went from 5% to 75%, smartphone penetration rose from 0% to 75%, and last-mile delivery via gig workers became possible).

Going back to first principles when analyzing a failure is critical. Overgeneralizing is easy. Thoughtful analysis is hard.

In the case of Spire, Peter Platzer and his co-founders had a deep and unique appreciation that nanosatellites and the coming newspace revolution addressed many of the deeper challenges of the original version of Iridium and traditional space. So much so that the original name for Spire was actually “NanoSatisfi”. Traditional satellites are the size of a car or school bus, can take 10 years to design and build, and cost close to $1 billion. Small satellites like the ones Spire builds, launches, and operates are the size of a shoebox, can take weeks to build and launch, and can cost as little as $100,000.

Smallsats can be 1,000x cheaper, 100x faster to build, and 100x smaller. The game had been changed on a fundamental level and smart newspace entrepreneurs like Spire’s Peter Platzer and Rocket Lab’s Peter Beck were paying attention.

#4 - “Auth0 must change its name to something that sounds better”

Every single developer understands Auth0’s name. Most non-developers do not.

Auth0 was never a hot consumer company or buzzy vertical SaaS company. It was a company by developers for developers. The Auth0 founding team of Eugenio Pace and Matias Woloski and then-CEO Jon Gelsey are hands-on developers who care deeply about their fellow developers having great tooling and intuitive interfaces.

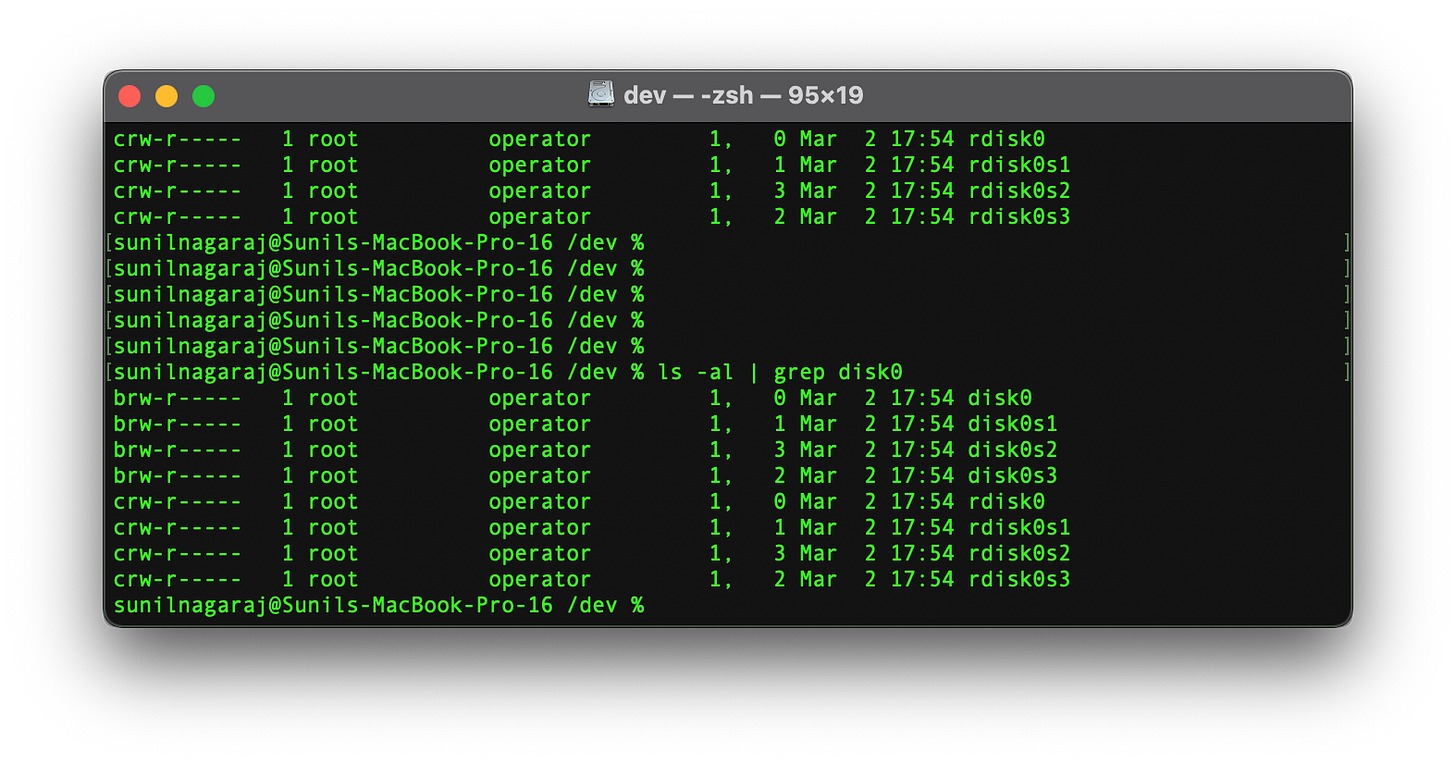

So what does “Auth0” mean? In Unix/Linux, various devices are connected to your computer as “device nodes” and show up within your machine’s “/dev/” folder. For example, your hard drive and its partitions are listed as “/dev/hda1” and “/dev/hda2” (or “/dev/disk0”, “/dev/disk1” if you’re on a Mac).

This nomenclature is so embedded in developer culture that another well-known developer company was actually named “/dev/payments” before it later renamed itself to “Stripe”.

Auth0 is a nerdy reference to the company’s goal of serving as a developer’s device node for identity and authorization -- “/dev/auth0”.

In an early Auth0 board meeting, I heard this ridiculous comment about dropping the Auth0 name, and it sounded like fingernails on a chalkboard with all the developers in the board room trading subtle glances.

In closing

It’s been one heck of a week with $12 billion of exits despite several years of ridiculous comments. Last week, I wrote about how Rocket Lab and Spire demonstrate the power of “software beyond the screen” and how Auth0’s $6.5b acquisition demonstrates the power of “nerdy and early” investing.

If you’ve made it this far, I hope this post helps you avoid saying ridiculous things to me and to others in the future :)

Are you a founder in the smart hardware or machine learning sector? Let’s talk! Leave a comment or get in touch with Ubiquity Ventures.

Ubiquity Ventures — led by Sunil Nagaraj — is a seed-stage venture capital firm focusing on early-stage investments in software beyond the screen, primarily smart hardware and machine intelligence applications.