Ubiquity Founder: Anuj Khandelwal of Empo Health (Bringing consumer design to digital health)

Learn how Empo Health's technology is working to prevent the 100,000 foot amputations related to diabetes annually in the US.

Today we spotlight a founder who leverages software beyond the screen to transform an industry. As always, each Ubiquity founder has their own nerdy background (we define nerdiness as having a deep obsession) that led to founding their startup.

Meet Anuj Khandelwal, CEO of Empo Health, a health platform working to prevent diabetic-related foot amputations through technology. Ubiquity Ventures invested in Empo Health seed round in late 2023.

Can you sum up what Empo Health does in one sentence?

At Empo, we're empowering podiatrists to detect early signs of diabetic foot ulcers through our novel full-color assistive imaging scale and accompanying remote patient monitoring platform, so the care team can address issues at the right time when it is least invasive and most cost-effective.

Tell us more about Empo Health’s product.

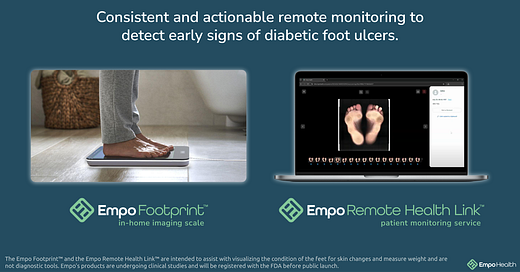

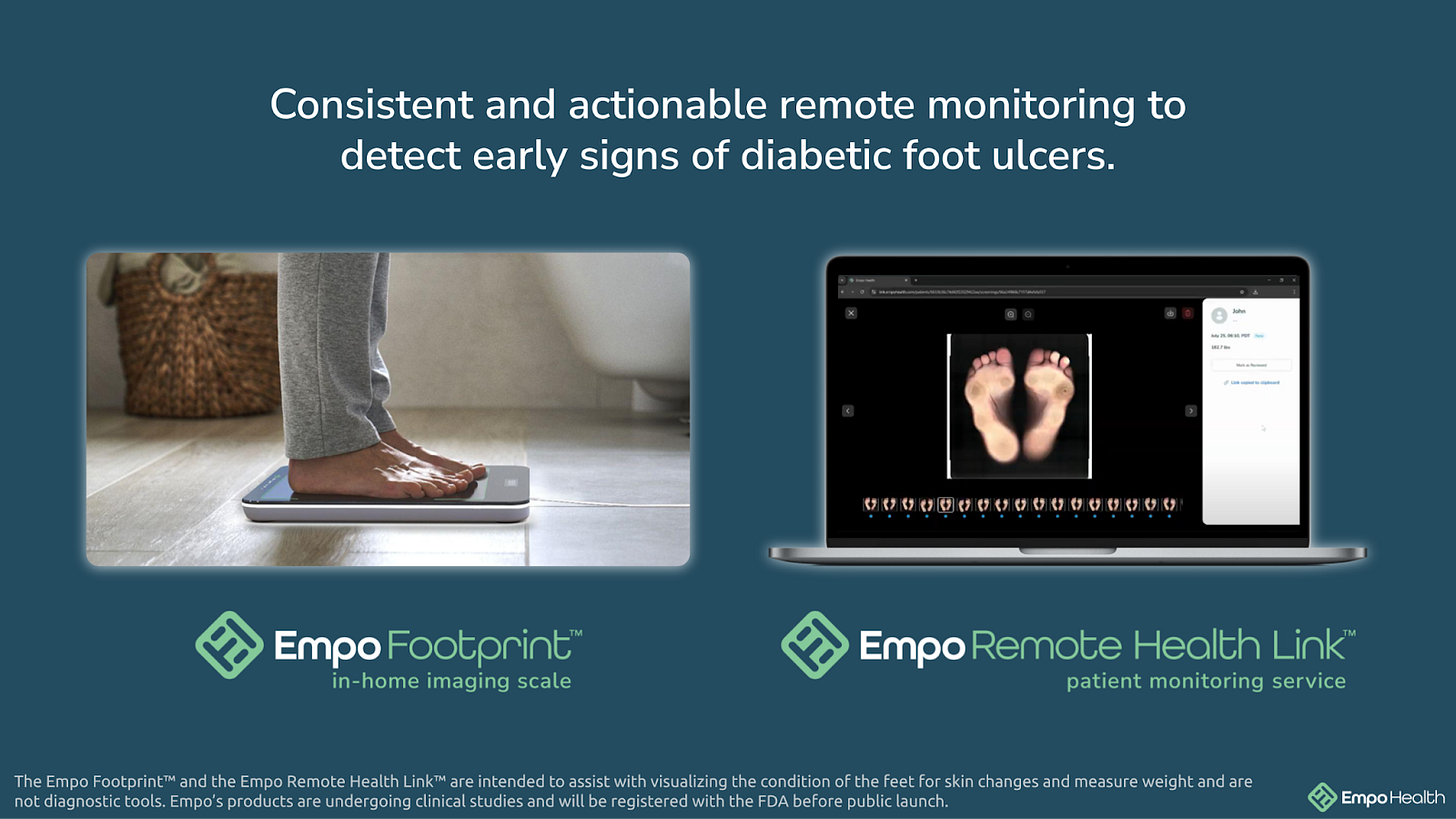

Our product has two components:

Empo FootprintTM, our in-home imaging scale

Empo Remote Health LinkTM, our overall remote patient monitoring service

The product will be registered with the FDA and launched to market early next year.

The Footprint is a device that we designed to assist with daily visual foot inspections for patients with diabetic neuropathy (patients who have lost protective feeling in their feet). It looks and functions like a typical weight scale, and when a patient steps on it, it also captures a full-color scan of the bottoms of their feet. It automatically uploads that data to the cloud through a built-in Wi-Fi or cellular data connection, and the patient and care team can review the data in the Remote Health Link web portal. They can act on an image if they see that a patient may have, for example, a pre-ulcerative lesion, a wound, or something else that indicates that they may be at risk for a diabetic foot ulcer.

What is the story behind the founding of Empo Health?

About four years ago, I was finishing up grad school at Stanford specializing in medical devices, and I got involved with the Stanford Biodesign program. The program had a really well-defined playbook on how to frame a medical problem and start a venture around it.

I reached out to my co-founder, Eric, who was actually my roommate from undergrad back at MIT. The two of us had been talking for a long time about potentially starting a medical device company one day; once we saw that the problem space and timing were right, we jumped on it.

I have a close family history of diabetes, so I’ve always been driven to tackle a diabetes-focused problem. Orthopedic problems have also been a major focus for me, especially since a brutal arm injury that derailed my college water polo career and causes lingering pain to this day after four surgeries. So the issue of diabetic foot ulcers and resulting amputations was a really personally-compelling blend of those two areas (diabetes + orthopedics). Moreover, we saw that the fundamental problem was about patient adherence to daily visual foot checks, and that the real solution had to be a blend of a new medical device that acted like a consumer product with a software service around it - really software beyond the screen. Marrying hardware and software was our area of specialty, and we saw that this was the kind of approach that would really allow us to help make a difference. Nobody to our knowledge has ever built a dataset of weight-bearing foot images over time like this, so the long-term applications like AI risk-prediction are really exciting too.

How did you notice the need for in-home health monitoring systems for patients with diabetes?

Beyond my family history, we interviewed dozens of clinicians across different specialties when vetting problem areas, and they kept bringing up this problem of patients losing feeling in their feet and then suffering foot ulcers. 50% of diabetics develop neuropathy, and half of those patients then experience a foot ulcer. There are over 100,000 amputations a year in the U.S. - over $40 billion a year - and within five years after an amputation, half of the patients die. The human costs are staggering, and so are the healthcare costs.

We saw that it was this massive problem, and a common thread that all of these podiatrists kept saying was that they needed consistent and actionable observations from patients’ homes. They were relying on patients visually inspecting their own feet every day for early signs of ulcers, and there were a lot of challenges with getting patients to do that reliably. That’s generally called “incompliance”, but I consider that a dirty word that puts the blame on the patient; in reality, it’s very difficult for patients in this category to prioritize their foot health when they have more seemingly pressing daily health concerns. Many of them lack the eyesight or flexibility to adequately see the bottoms of their feet, and still others lack the medical education to understand what they’re looking at.

We thought: it’s a no-brainer, we've got to make an in-home medical product that feels like a consistently easy-to-use consumer product for patients, providing actionable remote full-color images to podiatrists.

What failed attempts did you team try before arriving at the current solution?

There's the overall form factor of the Footprint and then there's the underlying technology.

We tried a bunch of different form factors that we thought might work before we ultimately settled on this weight scale idea. One of the ideas was an imaging bath mat that would sit outside a patient's shower; when they stepped on it and dried their feet, it would take an image of only their feet. We learned some really interesting things from in-home patient testing: because patients couldn't feel their feet, they couldn’t really tell that the device was drying their feet adequately. Instead, it was an unstable feeling for them to step on a hard surface with wet feet – even though there was no risk of slipping.

For the underlying technology, we prototyped pretty much every technology we could think of for imaging the feet to settle confidently on the way that we're doing it now.

We think of nerds as people who are obsessed with something. What are you nerdy about or obsessed with inside & outside of work?

I love physically building things. I spent countless hours in my neighbor’s woodshop as a child, which pointed me towards mechanical engineering alongside my interest in medicine from growing up in a family of physicians. After school, we'd be working on some new project or other, and it was a great chance to learn the ropes and become adept with machinery. There’s no better teaching experience as a child about shop safety than accidentally grabbing a hot branding iron with your full bare hand!

I enjoy working with anything from wood to metals to plastics, and then tying that into the electronics and programming side. Ultimately, I ended up training in mechatronics so I could come up with an idea, design the physical parts and circuits from scratch, build it, make it all work together functionally, and make it look nice. I've had the chance to do that for various projects over the years, whether for industry, coursework, gifts, or just for fun; I just really like building things.

What would you tell your past self if you could give them advice?

Now that I'm a few years into it, a framework that I wish I understood better at the beginning is how to deal with the categories of: “what I know I know”, “what I know I don't know”, and “what I don't know I don't know”. There are different formal concepts around this, but I’ll share how I think about it personally now as a founder and CEO.

One of my jobs is to keep expanding on the things that “I know I know” and to keep building on my competencies there. For the things that “I know I don't know”, I've got to bring on the right team around me who really know those areas well and lean on them, but I need to learn enough about it so that I can assign the right tasks and understand scope.

But that third category is the really nebulous one. Early on, I thought: I’m going to slowly shrink this bucket of things that “I don't know I don't know”; however, what I’ve realized over time is that no matter how much is uncovered, the bucket still continually expands as we grow to new stages with new corresponding challenges. I’ve got to keep chipping away at it by learning from the advisors, mentors, investors, and specialists around me, and being receptive to their feedback. But just as importantly, it’s about being confident in the things that I’m absolutely certain “I know I know” and holding fast to them, so that I can make the right decisions under uncertainty. That makes it possible to live well in that world of uncertainty, become comfortable with it, and communicate authentically to seek the best honest input.

What’s your advice to budding technical founders who haven’t yet taken the leap to launch their new company?

The toughest part about taking the leap is that it can be overwhelming figuring out where to start. I think that when you consider founding a venture, it feels maybe like you have to boil the ocean right away.

It’s worthwhile to launch a tech startup when you can picture a transformative idea or technology with a venture-scale business model. But if you just dive headfirst into trying to tackle everything right away, then it's overwhelming, inconsistent with funding pathways, and hard to understand the steps forward.

It’s more useful to think about things in terms of milestones and proof-points:

What's the first thing that I need to do to prove to myself that this idea has legs?

What do I need to do to prove to my intended customers that it has value?

What do I need to do to prove that I can actually build this or that the underlying tech works?

What do I need to do to prove it to investors, partners, and potential employees and recruit support around it?

When breaking it down into these different areas, it becomes a lot more reasonable to focus on the next steps while keeping the big picture in mind. Everything becomes more achievable and follows a more natural path for a startup to succeed.

Ubiquity Ventures — led by Sunil Nagaraj — is a seed-stage venture capital firm focused on startups solving real-world physical problems with "software beyond the screen", often using smart hardware or machine learning.

If your startup fits this description, fill out the 60-second Ubiquity pitch form and you’ll hear back shortly.