🕹️ When “Software Beyond the Screen” Kills

How Boeing’s MCAS System Took 346 Lives—and What Every Deeptech Startup Should Learn

In late 2018, a Boeing 737 MAX crashed shortly after takeoff, killing all 189 people aboard. Five months later, another 737 MAX went down under eerily similar circumstances. This time, 157 lives were lost.

Boeing’s first explanation? Faulty maintenance. Then pilot error.

The truth was far worse: A few lines of unruly software, shipped too quickly and shrouded in secrecy, were in command. And they would prove fatal.

Let’s unravel how this tragedy unfolded—and why every founder building “software beyond the screen” needs to take note.

💥 Two Crashes, Five Months Apart

On October 29, 2018, Lion Air Flight 610 departed Jakarta. Minutes into flight, a miscalibrated AoA sensor falsely told the plane it was climbing too steeply (too high angle of attack).

Boeing’s MCAS software kicked in and shoved the nose down. The pilots pulled back. MCAS activated again. And again.

They lost the fight. The jet plunged into the Java Sea. All 189 lives aboard were lost. (Wired)

Just five months later under nearly identical circumstances, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 suffered the same fate. These pilots did know about MCAS. They cut power to the system and attempted manual trim.

But at nearly 375 knots, the trim wheel was physically impossible to turn.(Leeham News)

The software wasn’t broken. The procedure wasn’t enough. And 157 more lives were lost.

⚔️ How We Got Here: Boeing vs. Airbus

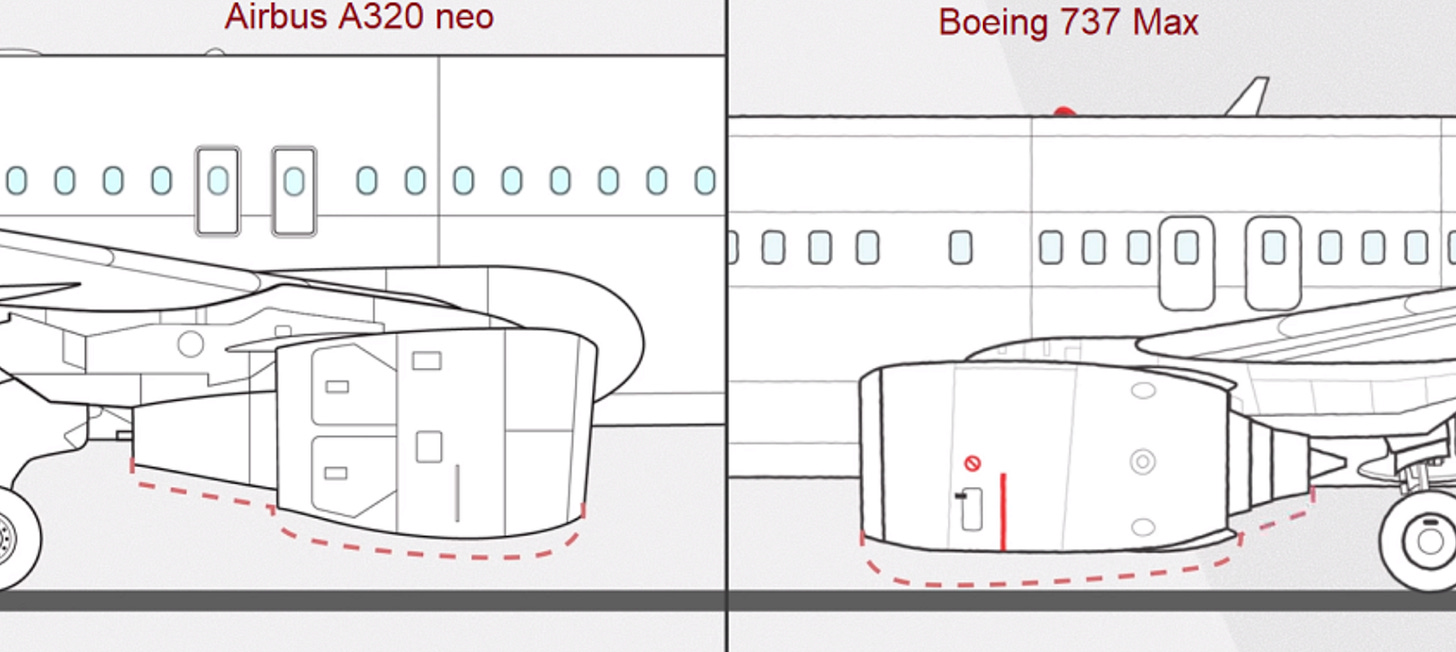

Rewind to the early 2010s. Airbus and Boeing were locked in a battle for fuel efficiency. Airbus upgraded the A320 with bigger, more efficient engines. Its taller landing gear made that easy.

But the Boeing 737 sat lower. Larger engines wouldn’t fit without scraping the tarmac.

Boeing’s solution? Mount the engines slightly farther forward and higher on the wing.

The change worked, on paper. But the tweak altered the plane’s handling characteristics. This would trigger a new “type rating” for its pilots, and Boeing knew its customers wanted to avoid any new pilot training or re-qualification for this 737 MAX model. Boeing had a choice: trigger a whole new training program and certification… or patch the problem in software.

⚙️ Enter MCAS: Small Code, Catastrophic Power

The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) was Boeing’s answer.

Its job: automatically nudge the nose down if it sensed a steep angle of attack. But it relied on data from just one sensor. And when triggered, it acted decisively, pushing the plane’s nose down hard, every five seconds, no matter what the pilots did.

To avoid the cost of pilot retraining, Boeing downplayed MCAS:

It was left out of pilot manuals (Wikipedia and New Yorker)

It could override human pilot input repeatedly (EveryCRSReport)

Its control authority was expanded late in development without reclassification

As the House Transportation Committee later wrote:

“MCAS was a software Band-Aid for a hardware problem—and it was engineered like one.”

🧠 Not a Glitch. A Culture Collapse.

This wasn’t a bug. MCAS performed exactly as written.

The real failure was upstream: a corporate culture that prioritized speed over safety and PR spin over transparency.

In 2020, internal Boeing emails were made public. One employee wrote:

“This airplane is designed by clowns, who in turn are supervised by monkeys.” (Fortune)

Others bragged about dodging simulator training requirements, even as they knew how complex and different the plane actually was. (Vanity Fair)

After the first crash, Boeing kept quiet. After the second, they couldn’t anymore.

📌 What Founders Should Take Away

At Ubiquity Ventures, we invest in real-world software—code that moves things, touches things, lifts, flies, cuts, diagnoses.

Boeing’s failure wasn’t exotic. It was a series of familiar shortcuts that added up to disaster. Five hard lessons:

Simplicity Can Kill

A “small patch” in MCAS altered how a jet behaved. Don’t confuse minimal code with minimal risk.Never Hide Critical Behavior

MCAS wasn’t mentioned in training to save costs. If your system changes user expectations, you must say so.Safety Must Be Systemic

Carve out time for broader analysis to systematically identify critical behavior. Leaders need to spend time to understand enough about each subsystem to properly assess the interactions. In this case, MCAS assumed pilots could override it. But at high speeds, that assumption broke down. If your safety plan only works in theory, it doesn’t work.Culture Eats Code

Engineers knew the risk. But the incentives said, “Ship it anyway.” When culture undermines caution, code becomes a weapon.Trust Is Asymmetric

Boeing spent decades building trust. They lost it in two crashes. Transparency may be expensive, but silence is lethal.

🔧 Beyond the Black Box

Boeing didn’t just ship broken software. They shipped a broken system, a legacy airframe jury-rigged to meet business needs, with code duct-taped on top.

The MCAS saga is a warning: when your code touches the physical world, it’s no longer “just software.” It becomes real, and so do the consequences.

In our earlier post, The Other Ring of Commitment, we argued that trust, not code, is the rarest commodity in the physical world. Boeing lost that trust not because their engineers made a coding mistake, but because their leadership ignored the consequences.

Ubiquity Ventures — led by Sunil Nagaraj — is a seed-stage venture capital firm focused on startups solving real-world physical problems with "software beyond the screen", often using smart hardware or machine learning.

If your startup fits this description, reach out to us.

Great point on the distinction between broken software and broken systems. Another case where what could have been a minor sensor issue cascaded into disaster was Air France 447: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air_France_Flight_447#Human_factors_and_computer_interaction

Liked the detailed explanation considering all the facts and publications !!!.